Last spring, the arid western edge of the Navajo Nation in Arizona was drier than it had been in many years. Feral and wild horses, dehydrated and malnourished, sought out a watering hole near Gray Mountain. Instead of finding relief, nearly 200 got stuck in muddy clay and perished.

It’s a scene that comes to mind for Carlee McClellan when he thinks about drought.

On the Navajo Nation, access to drinking water is limited, more than 40 percent of homes lack running water, and many people haul water over 50 miles by truck to replenish their storage cisterns. But if we want to understand what water, rain, and drought mean there, we need to think beyond household use.

Drought has a huge impact on agriculture, threatening the survival of plants and animals. McClellan grew up on the reservation practicing traditional dry farming, which relies on rainfall instead of irrigation and involves a variety of techniques for conserving scarce moisture. So, he knows how reliant his people are on crops and livestock like horses, cows, and sheep.

“Crops and livestock are an integral part of Navajo life,” said McClellan. “Water is important on many different levels beyond what you have coming into your home.”

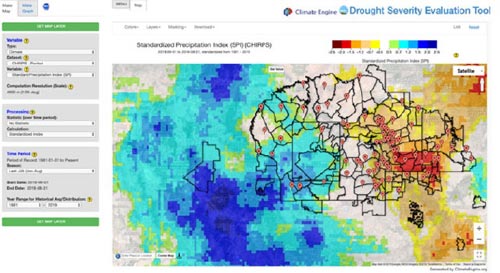

Those many levels explain why McClellan, senior hydrologist for the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources, is committed to developing the Drought Severity Evaluation Tool. The tool — a collaboration among NASA’s Western Water Applications Office (WWAO), the Navajo Nation, and the Desert Research Institute — is geared to helping the Navajo Nation improve its ability to monitor and report drought. It combines precipitation data from NASA satellites, drought indices, and on-the-ground rain measurements within a user-friendly web application.

Managing the water resources of the Navajo Nation is particularly difficult. With a population of over 200,000, it is the largest federally recognized sovereign tribe in the U.S. inland area. Located in the four corners region of the southwestern U.S., the Navajo Nation experiences frequent and pervasive droughts and variable precipitation patterns amid a backdrop of consistently rising temperatures. Declarations of drought emergencies are common, such as the one in 2018, when millions of drought-relief dollars were used to mitigate the issue.

Until now, McClellan and his team have relied on 85 rain gauges unevenly distributed across the Navajo Nation and just three satellite-based calculations made by NOAA’s Western Regional Climate Center. Rain-gauge monitoring is time-intensive and the limited data available can make it hard to assess precipitation across the Navajo Nation, a region the size of West Virginia with diverse geography ranging from low-lying desert to the San Juan River valley to the rain- and snow-prone forests of the Chuska Mountains.

Measures of precipitation can be improved by comparing the rain-gauge inputs to remotely sensed Earth observations such as those delivered by NASA. The Drought Severity Evaluation Tool will enable water managers to quickly calculate precipitation on the Navajo Nation for virtually any area (chapters, agencies, grazing districts, watersheds, ecoregions), over any historical time period in recent decades, in near-real-time.

When the Navajo Nation declares a drought emergency, area-specific data could be used to distribute relief funds. Currently, funds are divided evenly among the Nation’s 110 chapters (areas analogous to U.S. counties). But some chapters, especially in western areas, have less water and a greater need for funds. The Drought Severity Evaluation Tool will enable regional differences to be quantified and acted upon.

The tool can also generate reports and maps on the fly, showing precipitation for a specific chapter over the last 60 days, for example. Having such detailed, accurate, and current analyses will help officials and managers make more informed decisions not only in distributing relief funds, but also in planning for the future.